What is a Palomino?

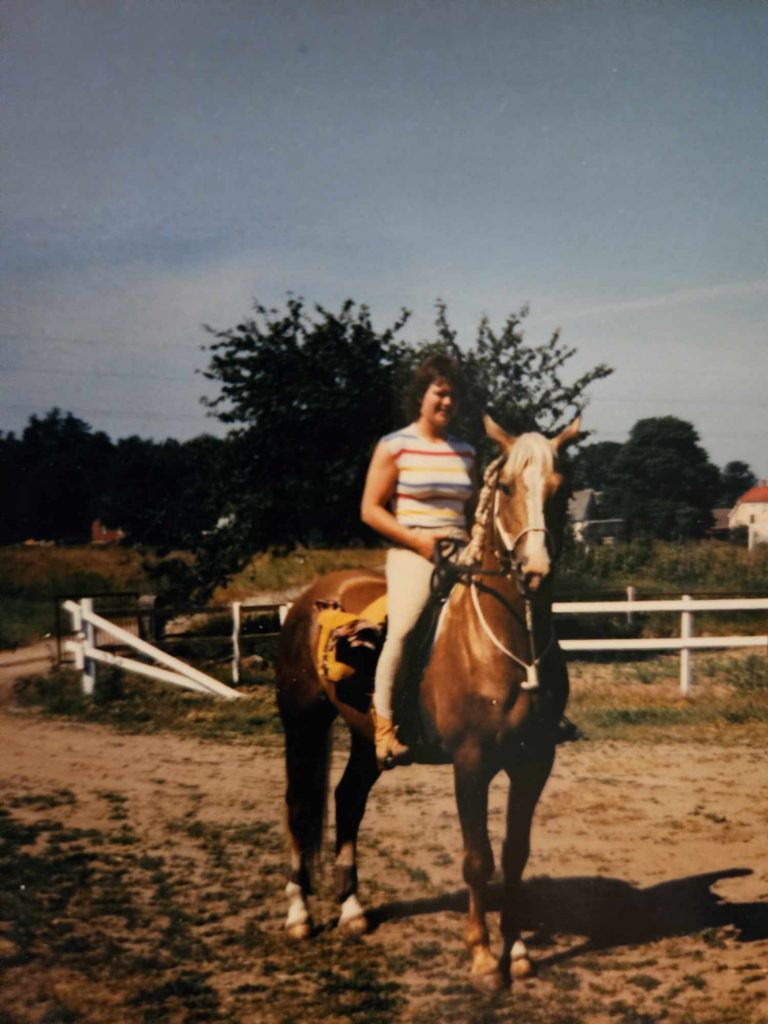

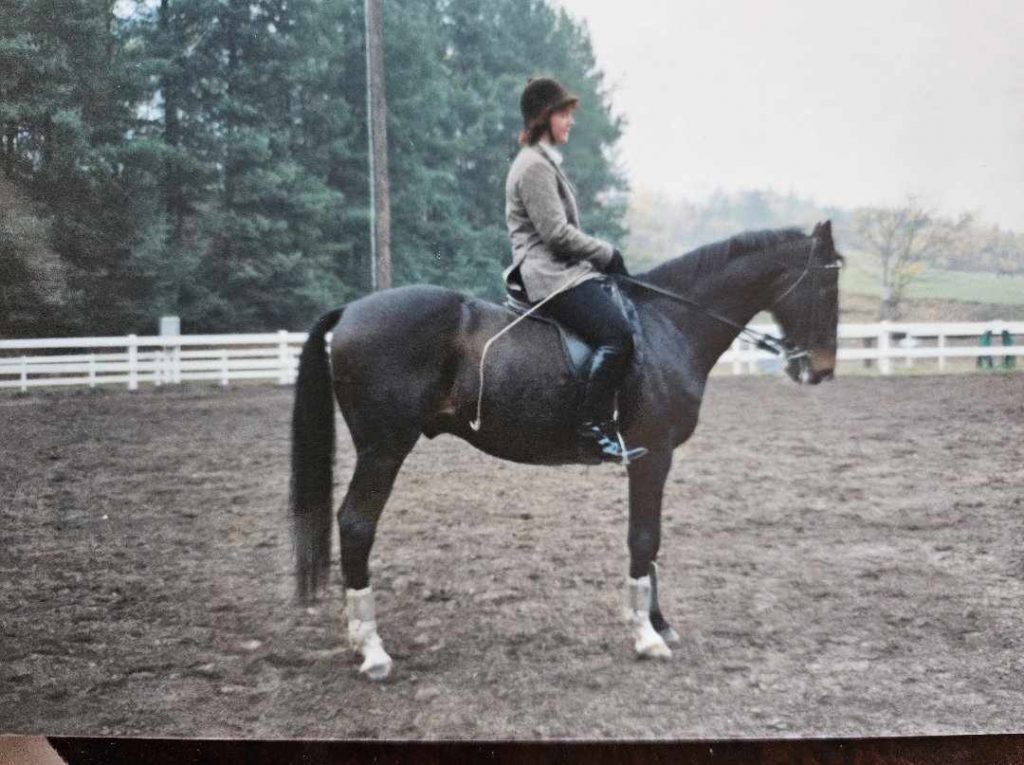

I’ve been breeding Palomino horses for almost 40 years of my life.

When I tell people that, the first thing they usually say is:

“Isn’t that just a color?”

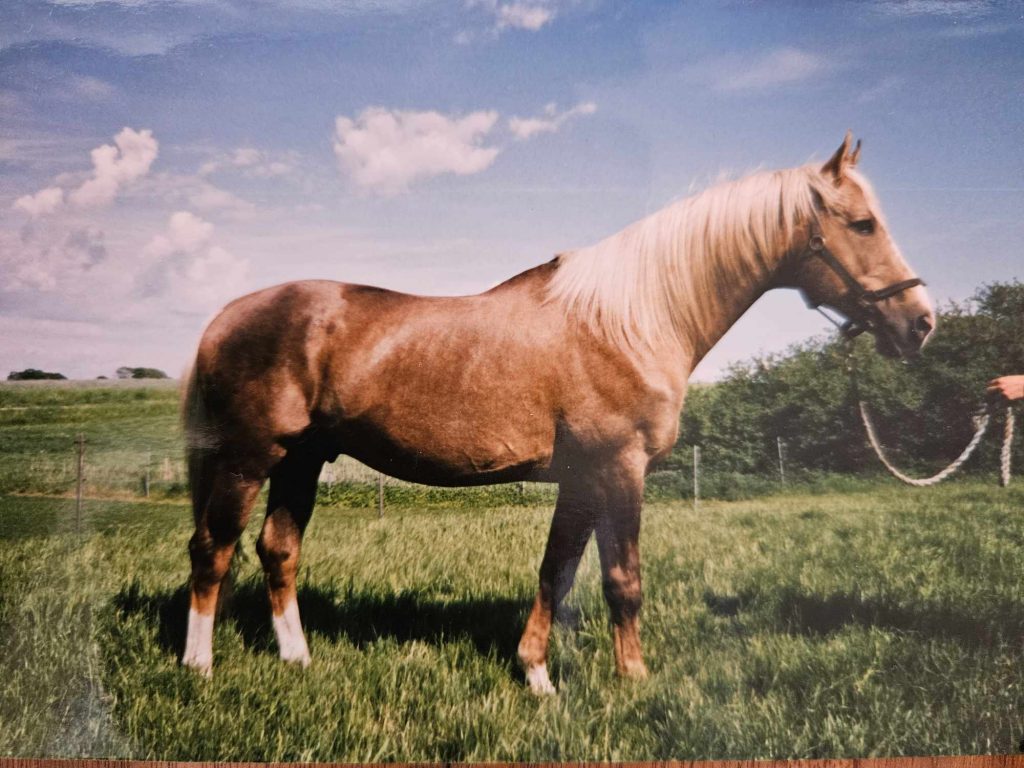

And yes – in a way, they’re right. In English, palomino refers to a horse with a golden body and a light, silvery mane and tail – or, as I like to describe them: gold-colored with a silver mane.

But what many don’t know is that Palomino can also be considered a breed.

Palomino is what we call a color breed – just like the Knabstrupper or the Pinto – where horses are bred not only for their color, but also for conformation, health, and performance. It’s not a single, uniform breed, but rather a type that can include many different sizes and backgrounds. The goal of Palomino breeding is to produce beautiful, healthy riding horses with good conformation – whether they’re big, small, ponies, or even miniature horses.

The Palomino breed exists in several countries, including the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark – but sadly, no longer in Sweden. When I lived in Sweden, we tried to establish a Swedish branch of the Danish association. It survived only as long as I served as chairperson – it takes a lot of energy and commitment to run an organization, and no one else was able to take over when I stepped down.

There was quite a bit of interest in Palominos at the time, especially when I was most active. In Swedish warmblood breeding, the palomino (or isabell as they call the color there) wasn’t very popular among judges. They preferred chestnuts and bays – colors more suited to the army’s needs. Pegasus and Pompe were gone, and only Bernstein carried the cream gene.

But among horse buyers, the color was always very popular. More than once, I’ve heard people say they dreamed of owning a palomino since they were children.

Today, Palominos are becoming more accepted in breeding programs, and golden horses are popping up everywhere – in breeds like the North Swedish, PRE, and warmbloods.

I started my Palomino breeding program with a stallion named Mackay, who I’ve written a lot about. He was a Swedish warmblood by Pegasus–Elektron, though he was never approved by the warmblood association. However, he was accepted by the Palomino registry. He sired many foals of all types, and many of them inherited his beautiful color.

It was never hard to sell foals that had the palomino color – but breeding is always a gamble. Two palominos can produce a chestnut foal, and those were sometimes harder to sell than the golden ones.

Two palominos can also produce a white foal, called a cremello. Cremellos have blue eyes and a white coat but still have skin pigment. It’s important not to confuse them with albinos. Albinos have red eyes and no pigment in the skin – and in fact, there are no true albino horses, even though some people think so.

Cremellos actually offer a genetic advantage:

If you breed a cremello mare with a chestnut stallion, the foal will always be palomino.

If you breed her to a bay stallion, the foal will always be buckskin (gold with black points).

This makes the cremello horse very valuable in breeding if you want to ensure the foals inherit the cream gene and get that special color.

If you’d like to learn more about Palomino horses, you can visit the website of the Danish Palomino Association:

👉 https://palomino-psa.dk/

Two of my own Palomino horses are still active in breeding in Sweden today, and it makes me so happy to see that the passion lives on – that others share the same love for these golden horses as I do.

If you’d like to see some of my horses through the years, feel free to visit my website:

👉 www.palomino.se