A Lifetime Struggle with Glasses

Everyone has their challenges, and mine has been my eyesight. I’ve been half-blind for most of my life, and as a kid, I was often called “four-eyes” in school. I got my first pair of glasses when I was eight—and I hated them. Not because I wasn’t grateful for being able to see, but with a -7 prescription in both eyes and astigmatism, my thick “bottle-bottom” lenses weren’t exactly flattering.

Back then, glasses were expensive. The lenses were partially covered by insurance, but the frames had to be paid for out of pocket. Since my eyesight kept changing as I grew, I needed new glasses every year. My parents accepted this, but they weren’t too happy when I needed more than one pair per year.

Horses and Glasses – A Bad Combination

As a child, I was constantly on the move (I probably would have been diagnosed with some attention disorder today), and glasses were always in the way—especially when I started riding horses. They got scratched, sat crooked, and fogged up every time it was cold or rainy.

When I turned 16, I was finally allowed to wear contact lenses. Soft lenses had just been introduced, and it felt like a revolution—a total game-changer!

But before that, I had my own “methods” for avoiding glasses, which often led to disaster.

The Great Catastrophe at Rudesjön

One summer, we were at our favorite swimming spot at Rudesjön. Large rocks stretched out into the water, allowing us to walk a bit before swimming to a small rock island further out, where we would sunbathe and dive into the deep water on one side.

One day, the water was a bit chilly, but I didn’t want to seem weak, so I jumped in and swam off—without thinking about my glasses still being on my face.

The moment I was underwater, I realized my mistake. When I surfaced, they were gone.

It was the middle of summer vacation, and getting a new pair wasn’t easy. I was devastated—spending the rest of the summer half-blind was not something I looked forward to.

My friend Eva-Lill tried helping me dive for them, but it was hopeless. The bottom was either rocky or covered in thick mud, and the water was so murky that we couldn’t see a thing.

When I got home and told my mom, I was completely discouraged. But shortly after, Eva-Lill’s father arrived on his bike—with a homemade “glasses rescuer”! He had bent the teeth of a leaf rake, attached it to a long handle, and suggested we try fishing for my glasses.

I didn’t have much hope, but after a while—miraculously—he fished them up! I had never been so happy to see my glasses again.

Short-Lived Happiness

My joy didn’t last long. Less than a week later, I left my glasses on the couch—and my unsuspecting brother sat on them. They snapped right in half.

With tape and glue (duct tape didn’t exist back then), we managed to fix them well enough. At least I could see again—for the time being.

But fate had more in store for my poor glasses.

The Riding Mishap That Sealed Their Fate

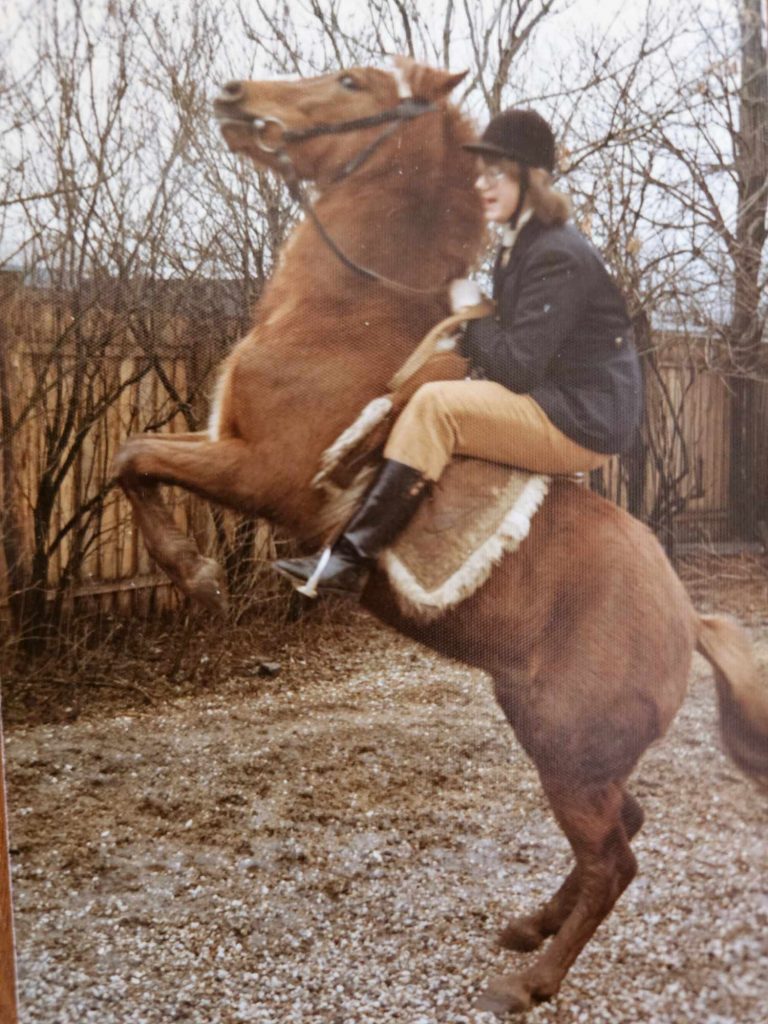

A few days later, I was out riding my beloved horse, Fatima. She was always energetic, and as we trotted down a narrow trail, I suddenly got a large pine branch straight in the face—knocking my glasses off… again.

Somehow, I managed to ride home without them. Then my mom and I went out searching. For some reason, she let me lead the way to show where I had lost them. That turned out to be a terrible idea.

Because suddenly, I heard a crunch under my foot.

I had stepped right on my glasses.

One lens was now shattered, and the frame was broken.

A Makeshift Solution

Now it was a real crisis. Trying to see with one eye while the other is blind makes you completely dizzy. We improvised—replacing the broken lens with a piece of cardboard and gluing the frame together again. It worked—barely.

A week later, my dad arrived with my old glasses from home so I could survive the rest of the summer. They weren’t perfect, but at least I could see—somewhat.

And so ended yet another chapter in the tragic life of my poor glasses.

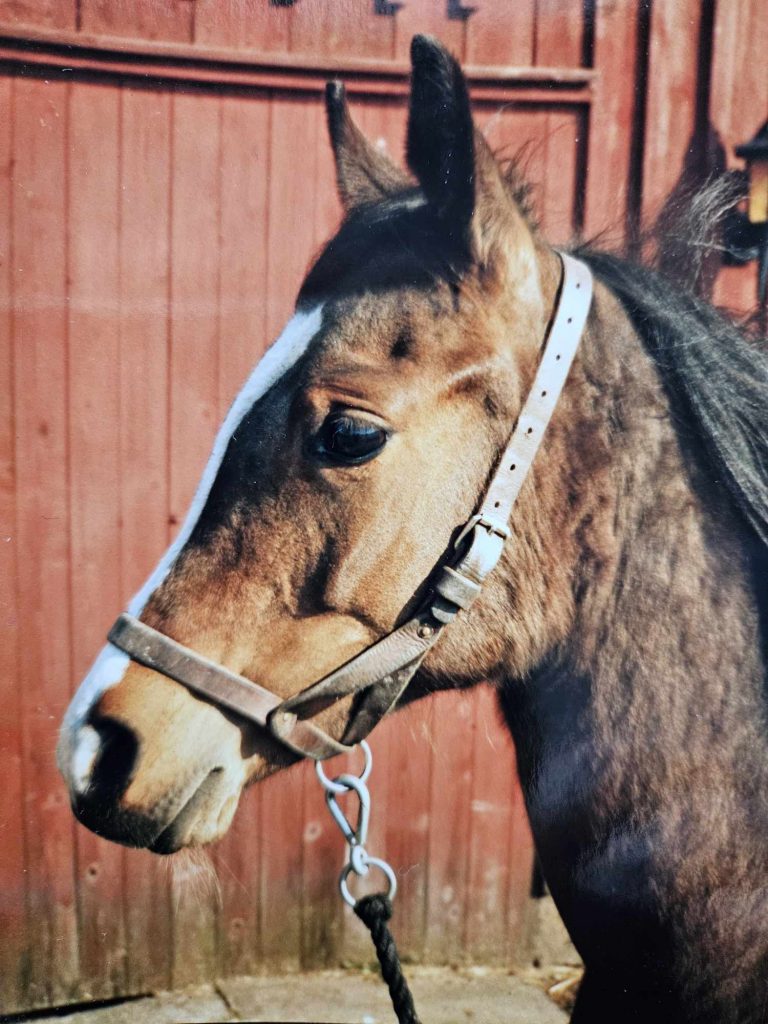

The photo is of me and Fatima! Without saddel and without glasses:)